Information Governance

good practice in handling, securing and protecting patient & employee data

DOWNLOADS

path: INFORMATION GOVERNANCE

- caldicott 7 principles.docx

- decision template tool for information data sharing – ukcgc.pdf

- information data sharing decision template ukcgc.pdf

- information governance user handbook.pdf

- information governance.pdf

- information handling – at a glance.doc

- police – disclosing information flowchart.pdf

- police – information sharing in homicide missing persons and other general enquiries.pdf

WEBLINKS

- UKCGC Information/Data Sharing Decision Template

- GMC on disclosing information for the protection of patient and others

- GMC on Confidentiality: good practice in handling patient information

- BMA: access to health records

- BMA: deatAdults at Risk and Disclosure of Information

- UK Caldicott Guardian Council on helping police to trace missing persons

- The Data Protection Act 2018;

- The Common Law Duty of Confidentiality;

- The Confidentiality NHS Code of Practice;

- The NHS Care Record Guarantee for England;

- The Social Care Record Guarantee for England;

- The Information Security NHS Code of Practice;

- The Records Management NHS Code of Practice;

- The Freedom of Information Act 2000.

What is Information Governance?

Information governance (IG) is the way in which the NHS (and YOU) handles all of its information, in particular the personal and sensitive information relating to patients and employees.

It provides a framework to ensure that personal information is dealt with legally, securely, efficiently and effectively, in order to deliver the best possible care.

It also offers NHS employees a clear structure to deal consistently with the many different rules about how information is handled.

Please note: The information provided here is for educational purposes only. You must always seek the latest guidance from the country you are operating in, and that onus is on you.

Most of the notes below have been derived from a workshop ran by UKCGC on Information Governance for General Practitioners in 2021 by Sandra Lomax (Vice Chair UKCGC), Chris Bunch (Chair UKCGC) and Christopher Fincken (Previous Member UKCGC, current member of INCANDVA)

The UKCGC - UK Caldicott Guardian Council

The UKCGC’s principal aim is to provide support for Caldicott Guardians and others fulfilling the Caldicott function within their organisation and:

- be a point of contact for all Caldicott Guardians and for health and care organisations seeking advice on the Caldicott principles;

- enable Caldicott Guardians to share information, views and experience;

- encourage consistent standards and training for Caldicott Guardians;

- help to develop guidance and policies relating to the Caldicott principles.

The services and support mechanisms offered by the Council are free and available to anybody who is a Caldicott Guardian or who fulfils the Caldicott function for their organisation as part of their wider role.

PLEASE MAKE SURE YOU/YOUR PRACTICE MANAGER IS USING THE DATA SECUIRTY AND PROTECTION TOOL KIT TO REPORT INCIDENTS TO THE ICO (INFORMATION COMMISSIONER’S OFFICE).

Let's talk CONFIDENTIALITY

Confidentiality is derived from a Latin set of words.

Con = WITH;

Fides = trust or faith;

Alitas/Alitatis = a nature, state or condition

Confidentiality = a condition with trust or faith

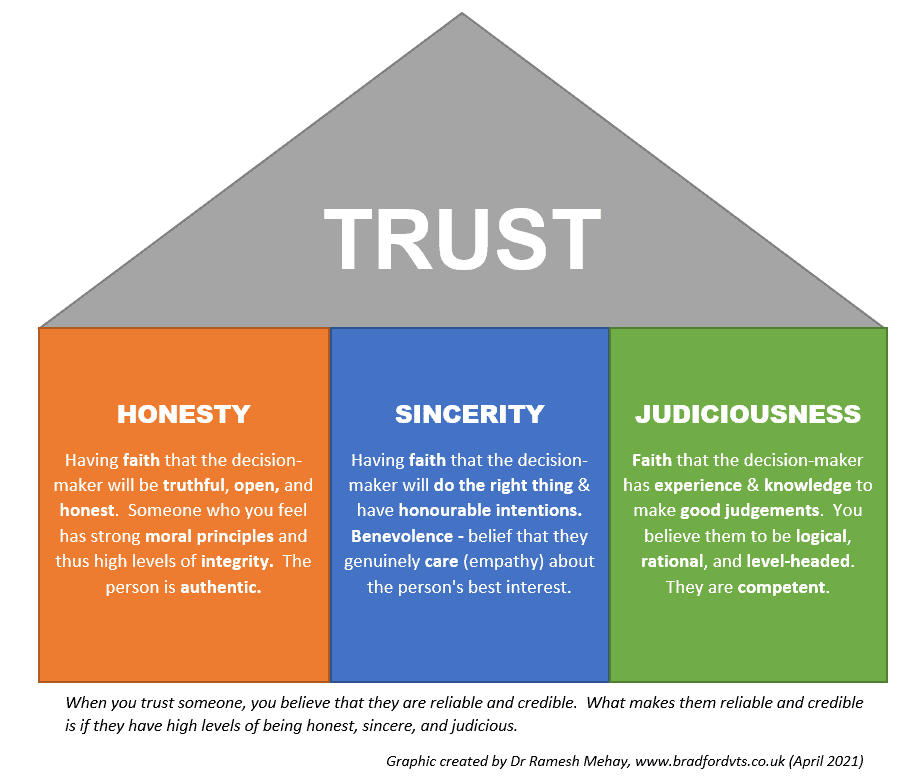

There are three components which help you to have TRUST in someone. These three components are Honesty, Sincerity and Judiciousness. If a person has strong positive traits in all three of these, then they become reliable and credible. Someone who is reliable and credible is trustworthy. Trust ensues.

Sweeney, a US Colonel pursuing a doctorate in Social Psychology, created the Three C’s of Trust – which are similar to the 3 things we describe here. He found 3 factors central to soldiers trusting their leaders. Character, Caring and Competence.

- Character – a bit like our honest, integrity and morality.

- Caring – in other words empathic towards the soldiers.

- Competent – skilled at doing the job.

- Sweeney found that each of the 3 C’s is necessary for trust, but none alone were sufficient.

“To be trusted is a greater compliment than being loved.”

― George MacDonald, Scottish author and poet

The Common Law Duty of Confidentiality/Confidence

The so-called common law duty of confidentiality essentially means that when someone shares personal information in confidence it must not be disclosed without some form of legal authority or justification.

So, you cannot disclose information unless the patient consent’s, there is vital interest, there is public interest or the doctrine of necessity. The starting point should always be not to disclose unless you have good legal or reasoning grounds.

The 7 Caldicott Principles

1. Justify the Purpose (s)

Every proposed use or transfer of personal-confidential data within or from an organisation should be clearly defined, scrutinised and documented with continuing uses regularly reviewed, by an appropriate guardian.

2. Don’t use personable identifiable information unless it is absolutely necessary

Personal confidential data should not be included unless it is essential for the specified purpose(s) of that flow. The need for patients to be identified should be considered at each stage of satisfying the purpose(s).

3. Use the minimum necessary personal confidential data

Where use of personal confidential data is considered to be essential, the inclusion of each individual item of data should be considered and justified so that the minimum amount of personal confidential data is transferred or accessible as is necessary for a function to be carried out.

4. Access to personal confidential data should be on a strict need-to-know basis

Only those individuals who need access to personal confidential data should have access to it, and they should only have access to the information items that they need to see. This may mean introducing access controls or splitting data flows where one data flow is used for several purposes.

5. Everyone with access to personal confidential data should be aware of their responsibilities

Action should be taken to ensure that those handling personal confidential data – both clinical and non-clinical staff are made fully aware of their responsibilities and obligations to respect patient confidentiality

6. Comply with the law. Every use of personal confidential data must be lawful.

Someone in each organisation handling personal confidential data should be responsible for ensuring that the organisation complies with legal requirements.

7. The duty to share information can be as important as the duty to protect patient confidentiality

Health and social care professionals should have the confidence to share information in the best interests of their patients within the framework set out by these principles. They should be supported by the policies of their employers, regulators and professional bodies.

The Duty of Candour

“When the personal data breach is likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons, the controller shall communicate the personal data breach to the data subject without undue delay.”

Let’s say an email about a patient has been sent to the wrong person via non-secure email. But the mistake has been recognised and corrected (emails deleted etc.)

- Would you tell the patient?

- What if the patient was comatose and terminally ill? Would you tell the relatives?

- What if it was after the patient had died? Would you tell the relatives?

Very few things are black or white.

- Remember, most email systems are secure. It is just that the NHS one is super secure and that is why you should be using that one over others.

- If sent to wrong recipient who was it sent to? For example, being sent to the wrong specialist doctor is less bad than it being sent to Joe Public.

- On the whole there is a duty of candour – which means one should be open and honest.

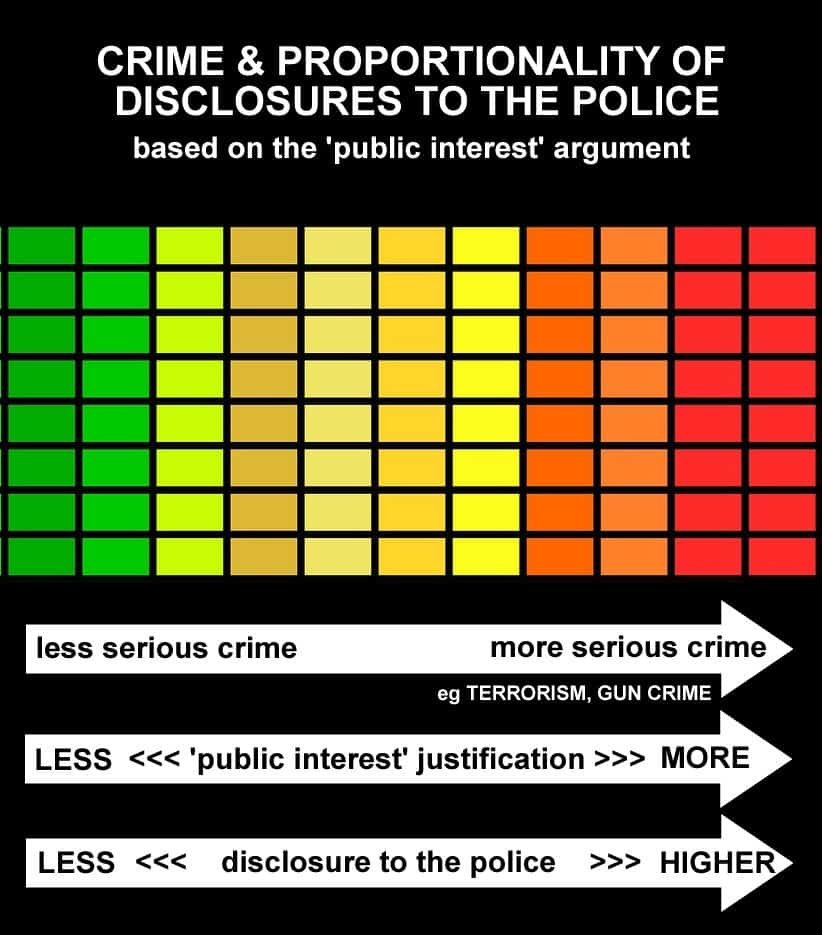

The Police asking you for records WITHOUT a court order, stating "in the public interest"

It is not uncommon for the police to approach your practice to ask for information relating to one of your patients. But remember, you are responsible for what you release. And do not automatically think that if the police are asking, then it must be okay for me to release. If you release something that is not permissible under law, then you (not the police) are held to account. If they have a court order – then generally you have to obey the court order – and then again – a court order is not permission to release everything – release what it tells you to release and what you feel is appropriate and relevant. But the problem comes when the police ask for information when there is NOT a court order. What do you do?

Here is some guidance for you.

- police – disclosing information flowchart.pdf

- police – information sharing in homicide missing persons and other general enquiries.pdf

- The GMC on disclosing information for the protection of patient and others

- GMC on Confidentiality: good practice in handling patient information

- UK Caldicott Guardian Council on helping police to trace missing persons

Let’s say the police ring you asking you for information about a patient who has killed another individual. They want more information about your patient WITHOUT a court order because it would take too long and time is of the essence and they’re saying it is “in the public interest” for you to release it. Do you?

And what if they said “please do not approach or inform the patient” – would you or would you not?

- First of all, don’t panic. There is always time for you to think and make your decision. You don’t have to make the decision ASAP. You will always have at least 15 minutes.

- Try not to make a decision on your own. Remember, you have your colleagues and the defence union that you can quickly call.

- The first thing to consider is what the public interest is. Ask them exactly how ‘it is in the public interest’ rather than them just furnishing you with a vague phrase. Unfortunately, there is no current public interest tool to help decide what is public interest. So try and work out what it is. For example, a patient roaming the streets randomly attacking people or involved in terrorist activity – YES, there is a ‘public interest’ to release information on that patient even without a court order because you have the greater duty of protecting others. But if the patient opened their car door and accidentally killed a person riding a bike – where is the public interest?

- If you do disclose anything, remember to disclose only the MINIMUM and RELEVANT information to satisfy the request.

- Generally wait for court order unless patient poses danger to life of others.

When is it Permissible to Disclose Information?

- When the person involved has given valid consent

- For consent to be valid, they must have mental capacity

- (a) be able to understand the information relevant to a particular decision

- (b) retain that information long enough to…

- (c) weigh up the balance of that information (e.g. weight the pros and cons of the various options, understand the benefits/risks/alternatives, understand the consequences of not doing or having something vs doing it or having it)

- (d) be able to communicate their decision in some way

- Be careful of coercion. Consent needs to be give freely. Is the person scared of someone else and hence made a decision to please them?

- Consider “Has decision-making been influenced by pain, fear, faith, love, loyalty, hope?”

- For consent to be valid, they must have mental capacity

- To protect the patient from harm

- For example if the patient is not of sound mind and a risk to themselves. Or perhaps they are vulnerable and need protection (persons who go missing are often vulnerable). Or a victim of know domestic violence?

- To protect others from harm

- Others like children, other household members, the public and so on.

- When the Law tells you to do so

- In certain cases of communicable disease, when you must inform the proper officer of your local authority.

- To comply with a statutory request made by a regulatory body such as the GMC .

- When specific crimes have been committed. For example, Terrorist activity. Crime involving knife and gunshot wounds. Accidental injury from, or self harm with, a knife or blade will not usually require notification. If you or your staff have been threatened or assaulted by a patient.

- If there is a Court Order for you to release information. Following an order made by a judge or presiding officer of a court.

- Remember, minimum necessary information. Release what you feel is relevant and appropriate. It does not always mean to release “everything”.

When considering risk to a patient or others, you do not have to prove that there was a risk to others, but that you had a genuine belief there was a risk to others. If you genuinely believe there is a risk to others, that gives you permission (not an edict) to release information.

By the way, also remember that a person’s capacity to consent can change. For example, they may have the capacity to make some decisions but not others, or their capacity may come and go. In some cases, people can be considered capable of making some decisions about their healthcare but not others.

General Advice to Approaching Any Data Release Matters

- First of all, don’t panic. Breathe!

- There is always time for you to think and make your decision. You don’t have to make the decision ASAP. You will always have at least 15 minutes.

- Don’t make the decision alone.

- Try not to make a decision on your own. Remember, you have your colleagues around you. Nearly all GP practices will have a Caldicott Guardian – locally or at CCG level.

- Also remember the defence union that you can quickly call.

- And if you have time before the requesting person needs a reply, contact the UKCGC. Use this link. Remember, do not disclose personal identifiable information.

- GMC Confidentiality Guidance

- You should, however, usually abide by the patient’s refusal to consent to disclosure, even if their decision leaves them (BUT NO ONE ELSE) at risk of death or serious harm.

- Ask yourself who are you protecting?

- Am I protecting an individual or a community/society?

- The Risk Appetite

- Consider the consequences of doing something versus NOT doing something.

- If you do disclose, only the MINIMUM NECESSARY and RELEVANT information to satisfy the request.

- Only disclose information that is relevant to the request, and only in the way required by the law.

- Tell patients about such disclosures whenever practicable

- Unless it would undermine the purpose of the disclosure to do so.

- Generally wait for court order

- Unless patient poses danger to life of others.

Use this 8-point Tool to help you…

- What is the issue in question?

- What pieces of law have been considered?

- (e.g. Data Protection Act, Common Law etc)

- What professional guidance has been considered?

- (e.g. General Medical Council )

- How have the Caldicott Principles been considered and satisfied?

- Who have I talked to?

- (Including professionals, sources of advice, the individual or their relatives)

- Is the information presented sufficient to make a decision or is more needed? Is urgency a factor?

- What is the rationale for the decision?

- (How are the different factors involved being considered )

- What is the decision?

- (Including: how it is to be implemented & whether it has been shared with the individual(s))?

Public Interest - what is that then?

There is not “public interest tool” available for you to work out if there is a risk to the public at large or not. So, hopefully the following guidance will help you. It is taken from point 68 from the GMC guidance for disclosures for the protection of patients and others. It says… When deciding whether the public interest in disclosing information outweighs the patient’s and the public interest in keeping the information confidential, you must consider:

- the potential harm or distress to the patient arising from the disclosure – for example, in terms of their future engagement with treatment and their overall health

- the potential harm to trust in doctors generally – for example, if it is widely perceived that doctors will readily disclose information about patients without consent

- the potential harm to others (whether to a specific person or people, or to the public more broadly) if the information is not disclosed

- the potential benefits to an individual or to society arising from the release of the information

- the nature of the information to be disclosed, and any views expressed by the patient

- whether the harms can be avoided or benefits gained without breaching the patient’s privacy or, if not, what is the minimum intrusion.

If you consider that failure to disclose the information would leave individuals or society exposed to a risk so serious that it outweighs the patient’s and the public interest in maintaining confidentiality, you should disclose relevant information promptly to an appropriate person or authority.

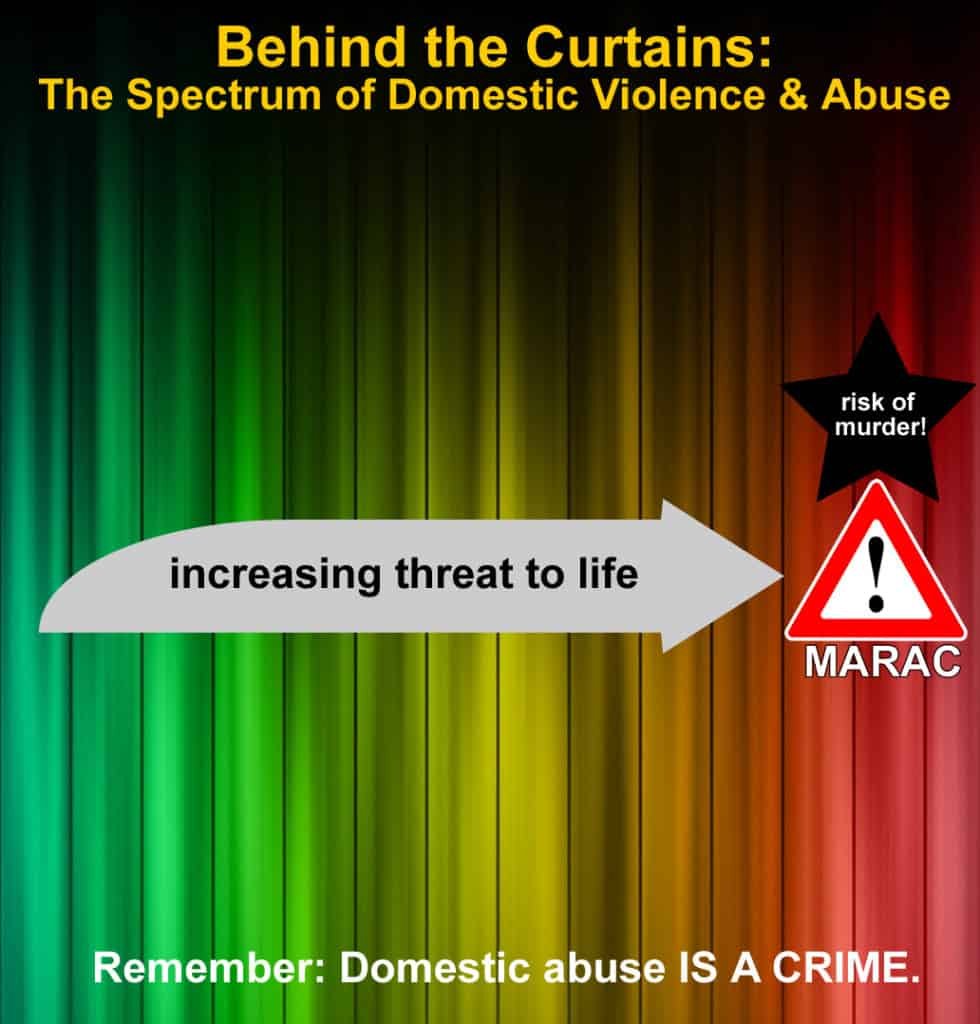

What about Domestic Violence then?

If a patient says they have been abused…

- Do not use word “alleges” as in “patient alleges Mr XXX assaulted him”.

- Why not use the word alleges? Because it seems to suggest/imply an element of not believing them – even though that is not our intention.

- Instead use the word “says”. “Patient says Mr XXX assaulted him”. Can you see the difference? And of course, don’t write “Mr XXX assaulted the patient” – because that implies Mr XXX did when in fact you were not there.

- It cannot be “ethically” justified if we hold information that we know could prevent serious harm to others and yet knowingly decide not to share it.

- A ground rule for Caldicott Guardians – all information shared about both victims and perpetrators must be in the context of the normal requirements of information sharing without consent, in this case on the basis of prevention and detection of crime or serious harm.

- In terms of proportionality, the more serious the harm the greater the imperative to prevent it and the greater the justification for sharing information without consent. It is difficult but important to try and quantify or measure the risk of potential harm. One way of doing this (in cases of domestic abuse) is to use the CAADA checklist . This process asks the individual victim 24 key questions, the responses are recorded. This process formalises the risk assessment process and provides key evidence in terms of justification when it comes to information sharing with other agencies.

Use the DASH toolkit to help you assess risk in Domestic Abuse, Stalking and Honour-based Violence. This assessment of risk should help you determine what to do next. Remember, seek help from other doctors/health professionals around you, your local safeguarding team and the medical defence union to which you belong.

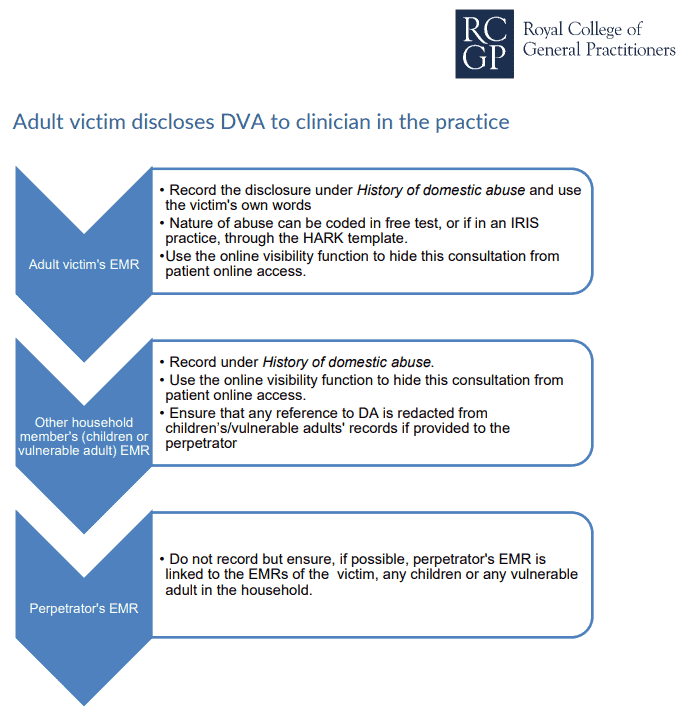

RECORDING DOMESTIC ABUSE IN THE MEDICAL RECORDS – RCGP (2021):

- “If you do code a consultation or communication as History of Domestic Abuse, as we recommend, this should be a major active problem until the abuse is resolved or the patient is presenting it as a past problem.

- “Be mindful that DA does not necessarily stop when a relationship ends.”

- “Also be mindful that the nature of DA can change over time so may always be relevant. The impact of DA can be significant on a victim’s long-term physical and mental health.”

- “Use the online visibility function to hide this consultation from patient online access”

- Full document here

What about information about someone who has died?

- Data Protection laws only apply to the living so are not relevant here.

- The common law duty of confidentiality still applies after death, so if it is known that the deceased had indicated that he did not wish any information about him disclosed, this should be respected.

A patient of yours died about a month ago. But the family are contesting the will. The family/executor approach you for access to the medical records.

What would you do?

- Stop, pause and breathe.

- This is a LEGAL issue – so, talk to your defence union. Seek professional legal advice.

- The Access to Health Records Act (1990) allows access to information in the deceased’s records for a patient’s representative and any other person who may have a claim arising out of the death, if it is directly relevant to the claim. BUT AGAIN, seek contact your defence union for advice before any disclosure

A couple of other scenarios

A young 15 year old girl asks the school nurse for contraception. She reveals she is sexually active with her 24 year old boyfriend and does not wish to get pregnant. She adores him and he adores her and then shows the nurse all things he has bought her including the latest top notch phone.

Should the nurse, breach confidentiality and report this? And if so, to who?

What the 24 year old is doing is illegal.

And there seems to be an element of grooming.

Report – Yes

To who? Child safeguarding team who can then advise further.

A 36-year old woman comes to see you so you can put it on record that she wants to die and her decision is to be respected.

She lost her husband 8 months ago from a terrible accident, has no dependents, and cannot live without him. She has tried. She has attempted suicide in the past but did not know how much paracetamol to take.

This time she says she is going to make it happen and states that she does not want any medical help. She feels she is of sound mind, and that the GP should not share the details of this consultation with anyone. She came because she wanted on record that she had actively decided this and was not depressed.

Should the GP breach confidentiality? If yes, to who?

A difficult one as people of sound mind are allowed to make irrational choices.

BUT the question is – is she of sound mind? How do you make an assessment of sound mind?

Therefore, should the GP breach confidentiality and involve the urgent psychiatry/crisis team to see if she is of sound mind or not and thus sectionable?

Remember, you can always talk to others – like in this case, the psychiatric team or the crisis team – discussing the case without revealing patient identifiable information first – and then proceed from there.

Forward this article on…